The Yavanas (Bactrian Greeks):

In the ancient Indian Hindu vocabulary the term Yavana stood for the Greeks. India experienced a second Greek invasion after the first one by the Macedonian Greek Alexander the Great when the Maurya Empire had fallen into pieces.

Alexander’s invasion of India, apart from its immediate consequences, left a long standing effect both in culture and the history of India. One of the most notable indirect consequences was the infiltrations and incursions of the Bactrian Greeks in the north-western India.

When the Mauryas had fallen on evil days and the Sungas were coming to power, the north-western and northern parts of India were conquered one after another by Greek rulers who were virtually the successors to the empire of Alexander in the easternmost part of his empire.

Bactria, modern Balkh, Old Persian Bakhdhi, Bakhal or Bakhli comprised the vast tract of land which was bounded on the south and the east by the Hindukush on the north by the river Oxus and on the west by modern regions of Merv and Herat. Thus it comprised greater part of modern Afghanistan.

Antiochus I:

On Alexander’s death, Seleucus secured for himself a large slice of Alexander’s Asiatic dominions with Syria as his Capital. Alexander had left a considerable number of Greek and Macedonian populations behind in Bactria. Antiochus I, son of Seleucus became a joint-ruler with his father and was placed in charge of Bactria (293 B.C.E.). Two years later on the death of his father (291 B.C.E.) he became sole king. Bactria was now under Governor Diodotus, and the adjoining province of Parthia was under Governor Arsaces.

Antiochus II:

Antiochus I Theos was succeeded by his son Antiochus II Soter. According to Justin, both Diodotus I and Arsaces revolted against Seleu-kidan rule and became independent.

Diodotus I: Diodotus II:

Diodotus died soon after and was succeeded by his son Diodotus II who reversed his father’s anti-Parthian policy and entered into an alliance with Arsaces. Antiochus’ successor Seleucus tried to reconquer Parthia but the alliance between Bactria and Parthia stood Arsaces in good stead and the independence of both Parthia and Bactria was saved.

When Diodotus died is not exactly known to us. But when Antiochus, king of Syria, proceeded with a large force to recover the Provinces of Bactria and Parthia, Euthydemus I was on the throne of Bactria. It is supposed that Diodotus II was dethroned and killed by Euthydemus who according to some writers, was related to Diodotus.

Euthydemus:

Euthydemus was involved in a long-drawn war with Antiochus III and finding his very existence in stake he proposed an honourable peace with Antiochus. It was impressed on Antiochus that Euthydemus was not a rebel; on the contrary, he put to death Diodotus and his children who belonged to the rebel family.

Further, if Syria and Bactria would be engaged in continued warfare the Scynthians would destroy both the countries. These arguments had good effects on Antiochus III who sent his son Demetrius to finalise the terms of the treaty. Antiochus was very much impressed; he recognised the independence of Bactria and cemented the friendship with Euthydemus who gave his daughter in marriage to Demetrius.

Antiochus III:

After making peace with Bactria, Antiochus III proceeded in an invasion of India and having crossed the Hindukush and entered into the Kabul Valley and encountered one ‘Sophagosenus, king of the Indians’. From the Indian sources we do not know who this Sophagosenus, i.e., Subhagasena was. According to the Tibetan historian, Taranath, he was connected with Virasena, king of Gandhara, who was the great-grandson of Asoka.

Antiochus was long absent from his capital in his not very decisive conflict with Parthia and Bactria and the threat of the expanding Roman Empire necessitated his return to Syria. He accepted a token submission of Subhagasena and quickly returned to his Capital leaving the formidable Bactrian power with a fresh lease of independence.

Subhagasena gave Antiochus ample supplies for his Forces and made over to him a number of war elephants but a large sum he promised to pay remained unrealised as Antiochus left in a hurry for his home which was in danger. His dream of reconquest of the lost provinces of the Seleukidan Empire thus remained unrealised.

We have no literary source to know whether Euthydemus carried his army towards the south beyond Hindukush, but numismatic evidence seems to prove that parts of Arachosia and the provinces to its north, Paropamisus and Aria, were conquered by him. It has been suggested by Gardner that the Bactrian Greek conquests in these regions were made under the auspices of Demetrius, the young and valiant son of Euthydemus, who probably ruled jointly with his father towards the end of his rule. However, nothing can be said with certainty.

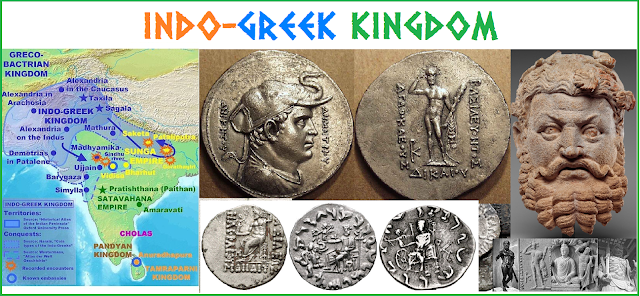

Under Euthydemus Bactria attained great prosperity as has been proved by numerous coins with his name and devices, made of gold, silver, copper, etc. Many of the coins of Euthydemus are masterpieces of numistic art and technique. Some of these with his figure show him to be a well-built man of strong individuality and firmness of character.

Demetrius:Demetrius, son of Euthydemus, about whom Polybius speaks in glowing terms, who was sent by his father to finalise the terms of peace with Antiochus III and made a deep impression on the latter, played a prominent part in the contemporary history of India and Bactria. It was Demetrius who after Alexander the Great, succeeded in carrying Greek arms into the interior of India.

His invasion was the first in the series of the Greek invasions which resulted in their permanent settlement in a substantial portion of north and north-west of India. India’s really intimate and prolonged Greek contact began with Demetrius.

Greco-Roman chroniclers like Strabo, Polybius, Justin, etc., have devoted pages to the career of Demetrius. In the Indian tradition although there is no clear mention of him yet a probable reference is found in the grammar of Patanjali and the Mahabharata in both of which mentions one Dattamitra, king of the Yavanas.

Much of the information obtained from the literary sources has been corroborated by the numerous coins of his time some of which bore legends both in Greek and Indian Prakrit, written in Greek and Kharosti characters prove beyond doubt that these were meant for circulation in his Indian possession.

Demetrius appears to have succeeded as the sole ruler of Bactria in his full manhood when Bactria was already a prosperous country. He was then 35 years of age with sufficient practical knowledge and experience of diplomacy, administration, etc., as his father’s deputy.

Political condition of the extreme north of India at the time was such that it invited the attention of the powerful neighbour Bactria. Demetrius crossed the Hindukush with a large army. His passage through the lands between the Hindukush and the Indus was facilitated due to their dependence and friendship with Bactrian Kingdom.

Demetrius conquered portions of the Punjab and Sind and probably founded cities there for the purpose of effective administration of the newly conquered territories. One of such cities has been referred to by Arrian and Ptolemy. While Arrian calls it Saggala, Ptolemy refers to it as Sagala which has been identified with Sakala, i.e., modern Sialkot in the Punjab.

During his Indian advance, Demetrius, like Alexander, settled Greek garrisons to protect his rear and flanks. These were called Demetrius as Alexander’s were called Alexandrias. These garrisons of Demetrius became the nuclei of several later Bactrian Greek settlements when their rule was confined to their Indian conquests only.

The exact extent of Demetrius’s advance into India is very much controversial and the information supplied by the Greek and the Indian texts have been interpreted in different ways. Strabo, basing his statement on Apollodorus remarks that the expansion of the Bactrian Kingdom in India was the work of both Demetrius and Menander, and that they conquered more nations than Alexander succeeded in conquering.

According to Strabo the Bactrian Chiefs, Menander and Demetrius conquered Patalene, i.e., the Indus delta, Saurastra (Saraostos), Cutch or Sagardvipa (Sigerdis). They extended their empire as far as Seres, that is, the land of the Chinese and Tibet in Central Asia, and Phryni, a Central Asian tribe. In one passage Strabo states that “those who came after Alexander advanced beyond the Hypanis to the Ganges and Palimbothra (Pataliputra)”.

The Indian texts like Yuga Purana and Patanjali’s Mahabhasya mention places such as Saketa (Oudh), Madhyamika (Modern Nagari in Rajasthan), Panchala (Rohilkhand), Mathura as conquered by the Greeks. But neither the Greek nor Indian source gives us the places conquered by Menander and Demetrius separately.

As Dr. J. N. Banerjee points out the Bactrian conquests were attributed to Menander by some scholars but subsequent researches have proved that it was Demetrius who had carried the Greek arms into the interior of India. According to W. W. Taru, both Apollodotus and Menander advanced into India under Demetrius. Menander came in by the great road across the Punjab and the Delhi passage to the Ganges and the Mauryan Capital Pataliputra; and Apollodotus down the Indus to its mouth and whatever might be beyond.

These two conquering forces were to converge on the centre of India and complete the circuit round northern India. According to him (Taru) Demetrius was the chief guiding factor in the enterprise and was helped by the other two who first acted as the sub-kings under Demetrius and later on succeeded him in different parts of India as independent kings.

Taru’s arguments, plausible though, are not corroborated by any literary evidence what is apparent from available evidence remarks N. K. Sastri textual as well as archaeological, in the fact, that of these Demetrius held alone Bactria as well as India, whereas the other two held sway in India only; their respective coin types leave no doubt about this.

However, Demetrius’ hold over Bactria was soon jeopardised and it became difficult for him to have effective control over so vast an empire from Bactria. The very extension of his dominion in India proved suicidal to him. In his absence, in Bactria Eucratides, whose antecedents are very little known and who is described by Justin as a leader of great vigour and ability, organised the Bactrian rebellion against Demetrius, put himself at the head of the rebels and made himself thus king.

To accomplish all this, there is no doubt, that Eucratides had a prolonged struggle against Demetrius and the memory of which is still preserved in the fragments of classical texts as well as in coins and commemorative medallions. It is also supposed by some writers that after having lost Bactria to Eucratides, Demetrius lived in India for the rest of his life. But nothing is known about the last days of Demetrius.

Demetrius’ association with India is borne out by archaeological as well as literary evidences. His coins with Greek legends on the obverse and Kharosti on the reverse may be referred to in this regard. Scholars have identified Dattamitra referred to in the Mahabharata with Demetrius. In Malakagnimitra Kalidasa also refers to invasion of India by the Greek at the time of Pushyamitra Sunga and the defeat of the Greeks at the hands of Vasumitra, son of Agnimitra and a general of Pushyamitra, on right bank of the river Sindhu.

Eucratides:

From the scanty references to the career of Eucratides in Strabo’s and Justin’s writings we know of his having overthrown Demetrius. Strabo mentions him to be the lord of a thousand cities but does not say whether the cities were in India or Bactria. Justin says he reduced India to subjection. This subjection of India probably means the land on the Sindhu.

From Justin’s remark it will not be unreasonable to suppose that some of the thousand cities referred to by Strabo were in India. But as Dr. D. C. Sarker points out Eucratides’ success in India was only partial and only temporary in regard to some of the areas. There is evidence to show that he had a series of fight with the princes of the house of Euthydemus who held possession of some parts of India and Afghanistan.

From the re-striking of some copper coins of Apollodotus by Eucratides raised the presumption that the former was defeated by the latter. From these coins scholars think that Apollodotus Soter was actually ousted from the Kapisa country. It is also possible that Eucratides had to fight with a number of the champions of the house of Demetrius after the latter’s death.

Numismatic evidence suggests that Heliocles was the son and successor of Eucratides and there are commemorative coins issued by Eucratides to celebrate his son Heliocles’ marriage with Laodice who was the daughter of Demetrius by his wife who was daughter of Antiocus III.

According to Justin, Eucratides had to fight not only with Demetrius, the champion of his house but also with the people known as Sogdians, i.e., the people of Sogdiana or the Bokhara region. Prolongs warfare told upon the health of Eucratides and totally exhausted he could ill afford to resist the attack of the Parthian king, Mithridates I who annexed two of Bactrian districts to his territory.

Justin mentions that when Eucratides was on journey homeward he was murdered by his son Heliocles. There is, however, a difference of opinion among scholars about the name of Eucratides’ murderer. According to Cunningham Apollodotus was the murderer, but researches have proved that he could not have been the murderer and Heliocles is generally accepted as the regicide.

Heliocles:

Heliocles is almost unanimously regarded as the successor of Eucratides. Our knowledge about his reign is probably the haziest. We have, however, two distinct groups of coins of his time, one of Attic (Greek) standard with only Greek legend and the other of bilingual type with both Greek and Indian languages.

A careful scrutiny of his coins has convinced scholars that Heliocles had given up the Attic standard coins and adopted the one in imitation of his father’s coin in Greek and Indian languages, after he had lost control on Bactria and his possessions were confined to Indian territories.

The anti-Bactrian policy initiated by the Parthian King Mithridates I who had occupied two districts of Bactria, was pursued with all vigour and according to a Roman historian Orosius Mithridates conquered all peoples between the Hydaspes and the Indus. This Hydaspes was not the Jhelum but the Medus Hydaspes, a Persian Stream. Thus the Parthian power seems to have extended from East Iran to the Indus. Strabo also mentions that the nomadic tribes Asii-Asiani, Saraucae-Sacae drove the Greeks out of Bactria. These tribes have been identified with the Yueh-chi and the Sakas.

Even if the above identifications are held doubtful, the fact remains that the Bactrian Kingdom was lost to the Greeks due to the invasions of the Parthians and the northern nomads. Heliocles, the last of the Greek Kings at Bactria, had to fall back into Kabu’ Valley and India. The Greek rule in these regions of Afghanistan and north-western India was characterised by internecine wars among various princes belonging to the houses of Demetrius and Eucratides.

More than 30 names of the Indo-Bactrian Greek rulers have been found from coins. For the majority of these rulers, their coins provide us with evidence- however, in the case of Apollodotus, Menander and Antialcidas ,we have quite substantial information.

Indo-Greek Rulers:

Apollodotus:

We have already come across the names of Apollodotus and Menander while discussing the Indian conquests of Demetrius. They ruled in regions south of the Hindukush and were perhaps related to the house of Euthydemus. The classical writers have mentioned Apollodotus twice in association with Menander. Some scholars suggest that he was perhaps the younger brother of Demetrius and might have been appointed along with Menander in conquering India.

The extent of the territories ruled by Apollodotus is not known for certain but from the Periplus we know that his territory extended from Kapisa and Gandhara and from western and southern Punjab to Sind and perhaps to the port of Barygaza (Broach). The Periplus also mentions that the coins, of both Apollodotus and Menander, were simultaneously in circulation at Broach. The very large number of the coins of Apollodotus discovered in wide expanse of territories show that he ruled over a vast kingdom.

Menander:

Strabo calls Menander, the greatest of the Indo-Greek Kings. According to Milindapanha, a Pali work in the form of a dialogue with Milinda (i.e., Menander), he was a mighty Yavana King of Sakala, modern Sialkot in the Punjab. The dialogue was between Menander and an erudite Buddhist scholar and monk named Nagasena in which Buddhist Metaphysics and Philosophy are discussed.

Milinda was an intelligent and acute questioner and being satisfied by the answers of Nagasena was so impressed that he became a convert to Buddhism. There is no doubt about the identification of Milinda with Menander. The classical writers like Strabo, Plutarch, Justin and Trogus mention Menander as a great personality.

The contemporary Buddhists held a very high opinion about him. Nagasena writes:

'As a disputant he was hard to equal, harder still to overcome, the acknowledged superior of all the founders of the various schools of thought. As in wisdom so in strength of body, swiftness and valour there was found none equal to Milinda in India. He was rich too, mighty in wealth and prosperity, and the number of his armed hosts knew no end.'

The unqualified praise lavished upon a foreign ruler shows the great esteem the alien monarch inspired in minds of the Indians.

W. W. Taru’s contention that Menander, belonging to a ruling house was not likely to adopt the creed of his subject people is not acceptable to scholars. There have been cases besides that of Menander, where the Greeks adopted Indian creeds. It was Menander alone who had left so deep an impress on the Indian mind that he was remembered with respect long after his time even during the 11th century B.C.E. when Kshemendra in his Avadanakalpalata makes a respectful mention of his name.

In the Milindapanha we have some interesting details about Menander. He is said to have been born in the village of Kalasi in the dvipa (island) of Alasanda, i.e., Alexandria, which was 200 yojanas away. The Pali work informs us that the King used to be attended by a large number of his Yonaka (Greek) courtiers when be met Nagasena.

Milindapanha also gives us a description of the capital of Menander. The country of the Yonaka, i.e., Greek King Menander, was a great centre of trade, a city that was called Sagala, i.e., Sakala (Sialkot) situated in a delightful country well watered and hilly, abounding in parks, gardens, groves, lakes and tanks, a paradise of rivers, mountains and woods.

Wise architects prepared the layout of the capital and its people did not know of any oppression since all enemies and adversaries had been put down. The defence of the City was strong, with many strong towers, ramparts and beautiful gates. The royal citadel is in the midst of the city which was walled and moated.

The streets were well-laid and there were crossroads, squares and market places. Costly merchandise of many varieties filled the shops. The city had hundreds and thousands of magnificent and very tall mansions. Streets were thronged by people, elephants, horses and carriages. Society had four classes of people—the Brahmanas, nobles, artificers and servants.

People showed respect to the master of all creeds. The shops dealt in Benares muslin, Kotumbara stuffs and clothes of other varieties. Sweet smell would issue from the markets where fragrant flowers and perfumes were on sale. Jewels were there in plenty, guilds of traders displayed their goods in the market.

We, however, cannot ascertain the exact nature of the relation of Menander with the house of Euthydemus. N. K. Sastri is of the opinion that in spite of what has been said about his royalty in the Milindapanha, Menander was a commoner perhaps related to the family of Euthydemus by marriage.

It is suggested that Menander’s dominions comprised Kabul Valley of Afghanistan, north-west India, Punjab, Sind, Kathiawar and Rajputana and perhaps parts of modern Uttarpradesh. It is also supposed that Menander had crossed the Hyphanis coast and reached the Isamus.

The Hyphanis has been identified with the Beas and the Isamus with Prakrit Ichchumai, a river of Panchala that runs through Kumayun Rohilkhand and the Kanauj region. The hold of Menander over Peshawar is borne out by Kharosti inscriptions discovered in the Bajaur tribal territory.

Under Menander Sakala became a shelter for the Buddhists who were persecuted under the rule of Pushyamitra Sunga.

According to Rapson the fame of Menander as a great and just ruler was not confined to India. Plutarch, writing two centuries after the death of Menander, described how, after his death in camp, the cities of his dominions contended for the honour of preserving his ashes. Rapson rightly points out that, It is thus as a Philosopher and not as a mighty conqueror that Menander, like Janmejaya, King of the Kurus and Janaka, King of Videha, in the Upanishads, has won for himself an abiding fame.

Strato-I: Strato-II:

At the time of his death in a camp, he was most probably engaged in warfare with some adversary, whose name is not known to us. He was succeeded by Strato-I who was a minor and the mother of the minor King worked as regent. Menander’s death adversely affected the fortunes of his dynasty and some parts of his dominions were lost almost immediately. Strato ruled for a long time and was succeeded by his grandson Strato-II and a large number of his silver coins have been discovered.

Antialcidas:

Antialcidas was another name that found prominence in the Indian epigraphic record at Besnagar. The inscription records the erection of Guruda-dhvaja, i.e., a column erected in honour of Lord Vasudeva, with a figure of Garuda as the capital by a Greek from Taxila named Heliodorus who had been sent by King Antialcidas as an ambassador to the court of the King Kaustiputra Bhagabhadra of the Sunga dynasty at Vidisa or Besnagar. This inscription testifies to the friendly relations that subsisted between the Yavana, i.e., Greek King of Taxila and the Sunga King of Vidisa, as well as to the adoption of Vaishnavism by the Greeks.

It is supposed that Antialcidas belonged to the Eucratides family and he succeeded Eucratides in the Kapisa region, as he issued coins with the image of the city divinity of Kapisa with which Eucratides himself restruck the coins of Apollodotus. In some of the coins found at Taxila, Antialcidas was associated with a senior ruler named Lysias who was probably his father. The rule of Lysias seems to have intervened between the reigns of Heliocles and Antialcidas.

It is sometimes suggested that Antialcidas, Lysias, Heliocles ruled simultaneously in different provinces like Taxila, Kapisa and Pushkaravati yet Dr. D. C. Sarkar points out that Antialcidas was the latest of all as he was a contemporary of King Bhagabhadra of Vidisa to whose Court he had sent an ambassador. According to Dr. D. C. Sarkar he sought friendship of Bhagabhadra against Menander.

Hermaeus:

Hermaeus was the last of the Kings of the Greek Dynasty of Eucratides. His kingdom was in the upper Kabul Valley which was surrounded by his enemy countries. The Sakas lay on the east, the Pahlavas, i.e., the Parthians on the west and the Yueh-chis on the north. Naturally, Hermaeus was hard put to the job of maintaining the security of his small kingdom.

His neighbouring Greek dominions of Puskaravati and Taxila had already been occupied by the Sakas and it was his turn to be dispossessed. To cope with the situation, he married Calliope who was related to Hippostratus of his rival house and sought to put up a united defence. But all this was of no avail and the barbarian blow to his Kingdom was soon to descend.

The contention of some earlier scholars that the final blow to Hermaeus’ Kingdom was administered by the Kushana (Yueh-Chi) king Kujala Kadphises is no longer accepted as correct. Some scholars also thought that Hemaeus sought the Kushana help in order to ward off the Parthian onslaught and the Kushanas who came as friends ultimately destroyed the King whom they came to help.

But according to N. K. Sastri and others, Hemaeus was overthrown by the Parthians or the Pahlavas and not the Kushanas. This is also borne out by the evidence of the coins. The Parthian King Gondophernes overthrew the Indo-Bactrian rule in India.

Dr. J. N. Banerjee considers that the second Greek conquest of India was more important than the first conducted by Alexander. Two centuries of cultural contact between the Greeks and the Indians was of immense consequences upon both sides. It was not merely a case of the Greek civilisation influencing the already highly developed Indian civilisation, but the reverse was equally true.

Religious ideals and ideas of the Indians had been adopted by the Greeks. We have seen how Nagasena’s answers to the searching intelligent questions of Menander made a deep impression upon the latter and he became i convert to Buddhism. The Pali work Milindapanha gives us the details of the deep religious and philosophical influence of Buddhism upon Menander.

Heliodorus was the Greek ambassador who became a worshipper of Vishnu and set up a Garuda column in honour of the deity at Besnagar. A great officer named Meridark Theodorus enshrined the relics of Buddha in the ancient country of Udayana, i.e., Surat Valley. There must have been more Greeks who became converts to Indian religions.

The Greeks also adopted the Indian way of life and living and gradually got identified with the sons of the soil. A second Theodorus, perhaps a descendant of Meridark Theodorus mentioned above caused a tank to be excavated at Udayana, in honour of all beings. In a stone relief depicting two wrestlers with a name Minandrasa below is Kharosti gives us a glimpse of Graeco-Indian secular life of the time.

In the realm of art the Bactrian Greeks made notable contributions. Die-cutters’ art reached perfection in Bactria and the skill with individual portraits on coins were incised and made the coins of the time the very best of the world. Although the degree of excellence had somewhat deteriorated after the Greeks settled in India yet the art was sufficiently potent to remodel indigenous currency. It was during Bactrian Greek occupation of India that the foundations of the Hellenic School of art of Gandhara were laid which reached its flowering during the Saka-Pahlava as also the early Kushana rule in India.

EDITED FROM historydiscussion.net

.png)