The Great Stupa at Sanchi is one of the oldest stone structures in India, and an important monument of Indian Architecture. It was originally commissioned by the emperor Ashoka in the 2nd century BCE. Its nucleus was a simple hemispherical brick structure built over the relics of the Buddha. The original construction work of this stupa was overseen by Ashoka, whose wife Devi was the daughter of a merchant of nearby Vidisha. Sanchi was also her birthplace as well as the venue of her and Ashoka's wedding. In the 1st century BCE, four elaborately carved toranas (ornamental gateways) and a balustrade encircling the entire structure were added. The Sanchi Stupa built during Mauryan period was made of bricks. The composite flourished until the 11th century.

The Ashoka pillar

The upper part of the Ashoka pillar in Sanchi ( left ). The image on the right is a representation of its original condition.

. . . path is prescribed both for the monks and for the nuns. As long as (my) sons and great-grandsons (shall reign ; and) as long as the Moon and the Sun (shall endure), the monk or nun who shall cause divisions in the Sangha, shall be compelled to put on white robes and to reside apart. For what is my desire ? That the Sangha may be united and may long endure.

— Edict of Ashoka on the Sanchi pillar.

The pillar, when intact, was about 42 feet in height and consisted of a round and slightly tapering monolithic shaft, with bell-shaped capital surmounted by an abacus and a crowning ornament of four lions, set back to back, the whole finely finished and polished to a remarkable luster from top to bottom. The abacus is adorned with four flame palmette designs separated one from the other by pairs of geese, symbolical perhaps of the flock of the Buddha's disciples. The lions from the summit, though now quite disfigured, still testify to the skills of the sculptors.

The sandstone out of which the pillar is carved came from the quarries of Chunar several hundred miles away, implying that the builders were able to transport a block of stone over forty feet in length and weighing almost as many tons over such a distance. They probably used water transport, using rafts during the rainy season up the Ganges, Jumna and Betwa rivers.

Temple 40

Another structure which has been dated, at least partially, to the 3rd century BCE, is the so-called Temple 40, one of the first instances of free-standing temples in India. Temple 40 has remains of three different periods, the earliest period dating to the Maurya age, which probably makes it contemporary to the creation of the Great Stupa. An inscription even suggests it might have been established by Bindusara, the father of Ashoka.The original 3rd century BCE temple was built on a high rectangular stone platform, with two flights of stairs to the east and the west. It was an apsidal hall, probably made of timber. It was burnt down sometime in the 2nd century.

Later, the platform was enlarged to and re-used to erect a pillared hall with fifty columns (5x10) of which stumps remain. Some of these pillars have inscriptions of the 2nd century BCE. In the 7th or 8th century a small shrine was established in one corner of the platform, re-using some of the pillars and putting them in their present position.

Shunga period

On the basis of Ashokavadana, it is presumed that the stupa may have been vandalized at one point sometime in the 2nd century BCE, an event some have related to the rise of the Shunga emperor Pushyamitra Shunga who overtook the Mauryan Empire as an army general. It has been suggested that Pushyamitra may have destroyed the original stupa, and his son Agnimitra rebuilt it. The original brick stupa was covered with stone during the Shunga period.

Given the rather decentralized and fragmentary nature of the Shunga state, with many cities actually issuing their own coinage, as well as the relative dislike of the Shungas for Buddhism, some authors argue that the constructions of that period in Sanchi cannot really be called "Shunga". They were not the result of royal sponsorship, in contrast with what happened during the Mauryas, and most of the dedications at Sanchi were private or collective, rather than the result of royal patronage.

Great Stupa (No 1)

During the later rule of the Shunga, the stupa was expanded with stone slabs to almost twice its original size. The dome was flattened near the top and crowned by three superimposed parasols within a square railing. With its many tiers it was a symbol of the dharma, the Wheel of the Law. The dome was set on a high circular drum meant for circumambulation, which could be accessed via a double staircase. A second stone pathway at ground level was enclosed by a stone balustrade. The railings around Stupa 1 do not have artistic reliefs. These are only slabs, with some dedicatory inscriptions. These elements are dated to circa 150 BCE or 175-125 BCE.

Although the railings are made up of stone, they are copied from a wooden prototype, and as John Marshall has observed the joints between the coping stones have been cut at a slant, as wood is naturally cut, and not vertically as stone should be cut. Besides the short records of the donors written on the railings in Brahmi script, there are two later inscriptions on the railings added during the time of the Gupta Period. Some reliefs are visible on the stairway balustrade, and are dated to 125-100 BCE. Some authors consider that these reliefs, rather crude and without obvious Buddhist connotations, are the oldest reliefs of all Sanchi, slightly older even than the reliefs of Sanchi Stupa No.2.

Stupa No2: the first Buddhist reliefs

The stupas which seem to have been commissioned during the rule of the Shungas are the Second and then the Third stupas , following the ground balustrade and stone casing of the Great Stupa (Stupa No 1). The reliefs are dated to circa 115 BCE for the medallions, and 80 BCE for the pillar carvings, slightly before the reliefs of Bharhut for the earliest, with some reworks down to the 1st century CE.

Stupa No2 was established later than the Great Stupa, but it is probably displaying the earliest architectural ornaments. For the first time, clearly Buddhist themes are represented, particularly the four events in the life of the Buddha that are: the Nativity, the Enlightenment, the First Sermon and the Decease.

A medallion made in Stupa no.2 circa 115 BCE.

Stupa No. 3

Stupa No.3 was built during the time of the Shungas, who also built the railing around it as well as the staircase. The Relics of Sariputra and Mahamoggallana, the disciples of the Buddha are said to have been placed in Stupa No 3, and relics boxes were excavated tending to confirm this.The reliefs on the railings are said to be slightly later than those of Stupa No.2.

The Shunga Pillar

Shunga pillar. The capital of the pillar is visible to the side.

Pillar 25 at Sanchi is also attributed to the Shungas, in the 2nd-1st century BCE, and is considered as similar in design to the Heliodorus pillar, locally called Kham Baba pillar, dedicated by Heliodorus, the ambassador to the Indo-Greek king Antialkidas, in nearby Vidisha circa 100 BCE.That it belongs to about the period of the Shunga, is clear from its design and from the character of the surface dressing.

The Heliodorus pillar in nearby Vidisha,India.

The height of the pillar, including the capital, is 15 ft, its diameter at the base 1 ft. 4 in. Up to a height of 4 ft. 6 in. the shaft is octagonal; above that, sixteen-sided. In the octagonal portion all the facets are flat, but in the upper section the alternate facets are fluted, the eight other sides being produced by a concave chamfering of the arrises of the octagon. This method of finishing off the arris at the point of transition between the two sections are features characteristic of the second and first centuries BCE. The west side of the shaft is split off, but the tenon at the top, to which the capital was mortised, is still preserved. The capital is of the usual bell-shaped Persepolitan type, with lotus leaves falling over the shoulder of the bell. Above this is a circular cable necking, then a second circular necking relieved by a bead and lozenge pattern, and, finally, a deep square abacus adorned with a railing in relief. The crowning feature, probably a lion, has disappeared.

Satavahana period

Western gateway of the stupa

From the 1st century BCE, the highly decorated gateways were built, the work being apparently commissioned by the Satavahana. The balustrade and the gateways were also colored. The gateways/toranas are generally dated to the 1st century CE.

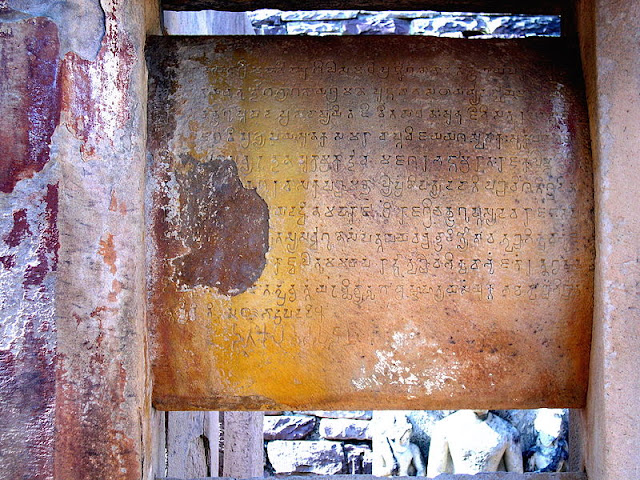

The Siri-Satakani inscription in the Brahmi script records the gift of one of the top architraves of the Southern Gateway by the artisans of the Satavahana king Satakarni:

𑀭𑀦𑁄 𑀲𑀺𑀭𑀺 𑀲𑀢𑀓𑀦𑀺𑀲 (Rano Siri Satakanisa)

𑀅𑀯𑀲𑀦𑀺𑀲 𑀯𑀲𑀺𑀣𑀺𑀧𑀼𑀢𑀲 (avesanisa vasithiputasa)

𑀅𑀦𑀁𑀤𑀲 𑀤𑀦𑀁 (Anamdasa danam)"

"Gift of Ananda, the son of Vasithi, the foreman of the artisans of rajan Siri Satakarni"

— Inscription of the Southern Gateway of the Great Stupa

There are some uncertainties about the date and the identity of the Satakarni in question, as a king Satakarni is mentioned in the Hathigumpha inscription which is sometimes dated to the 2nd century BCE. Also, several Satavahana kings used the name "Satakarni", which complicates the matter. Usual dates given for the gateways range from 50 BCE to the 1st century CE.Another early Satavahana monument is known, Cave No.19 of king Kanha (100-70 BCE) at the Nasik caves, which is much less developed artistically than the Sanchi toranas.

Although made of stone, the torana gateways were carved and constructed in the manner of wood and the gateways were covered with narrative sculptures. It has also been suggested that the stone reliefs were made by ivory carvers from nearby Vidisha, and an inscription on the Southern Gateway of the Great Stupa ("The Worship of the Bodhisattva's hair") was dedicated by the Guild of Ivory Carvers of Vidisha.

Inscription "Vedisakehi daṃtakārehi rupakaṃmaṃ kataṃ" (𑀯𑁂𑀤𑀺𑀲𑀓𑁂𑀨𑀺 𑀤𑀁𑀢𑀓𑀸𑀭𑁂𑀨𑀺 𑀭𑀼𑀧𑀓𑀁𑀫𑀁 𑀓𑀢𑀁,

The inscription reads: "Vedisakehi damtakārehi rupakammam katam" meaning "The ivory-workers from Vidisha have done the carving".Some of the Begram ivories or the "Pompeii Lakshmi" give an indication of the kind of ivory works that could have influenced the carvings at Sanchi.

The reliefs show scenes from the life of the Buddha integrated with everyday events that would be familiar to the onlookers and so make it easier for them to understand the Buddhist creed as relevant to their lives. At Sanchi and most other stupas the local population donated money for the embellishment of the stupa to attain spiritual merit. There was no direct royal patronage.

On these stone carvings the Buddha was never depicted as a human figure, due to aniconism in Buddhism. Instead the artists chose to represent him by certain attributes, such as the horse on which he left his father’s home, his footprints, or a canopy under the bodhi tree at the point of his enlightenment. The human body was thought to be too confining for the Buddha, before the Greek artists started to depict him in human form.

Architecture: evolution of the pillar capital

Similarites have been found in the designs of the capitals of various areas of northern India from the time of Ashoka to the time of the Satavahanas at Sanchi: particularly between the Pataliputra capital at the Mauryan Empire capital of Pataliputra (3rd century BCE), the pillar capitals at the Sunga Empire Buddhist complex of Bharhut (2nd century BCE), and the pillar capitals of the Satavahanas at Sanchi (1st centuries BCE/CE).

The earliest known example in India, the Pataliputra capital (3rd century BCE) is decorated with rows of repeating rosettes, ovolos and bead and reel mouldings, wave-like scrolls and side volutes with central rosettes, around a prominent central flame palmette, which is the main motif. These are quite similar to Classical Greek designs, and the capital has been described as quasi-Ionic.Greek influence seems more than prevalent here.

The Sanchi Pillar of Ashoka, of roughly the same period, also has a central flame palmette design on a square-section central pillar, but this time, surrounded by lions, in the same way as many of the other Pillars of Ashoka.

The pillar capital in Bharhut, dated to the 2nd century BCE during the Sunga Empire period, also incorporates many of these characteristics, with a central anta capital with many rosettes, beads-and-reels, as well as a central palmette design. Importantly, recumbent animals (lions, symbols of Buddhism) were added, in the style of the Pillars of Ashoka.

Bharhut pillar capital

Greek devotees

Some of the friezes of Sanchi show devotees in Greek attire.The men are depicted with short curly hair, often held together with a headband of the type commonly seen on Greek coins. The clothing too is Greek, complete with tunics, capes and sandals, typical of the Greek travelling costume.The musical instruments are also quite characteristic, such as the double flute called aulos. Also visible are carnyx-like horns.

Northern gateway of the stupa

The actual participation of Yavanas/Yonas (Greek donors) to the construction of Sanchi is known from three inscriptions made by self-declared Yavana donors:

The clearest of these reads "Setapathiyasa Yonasa danam" ("Gift of the Yona of Setapatha")- Setapatha being an uncertain city, possibly a location near Nasik, a place where other dedications by Yavanas are known, in cave No.17 of the Nasik caves complex, and on the pillars of the Karla caves not far away.

A second similar inscription on a pillar reads: "[Sv]etapathasa (Yona?)sa danam", with probably the same meaning, ("Gift of the Yona of Setapatha").

The third inscription, on two adjacent pavement slabs reads "Cuda yo[vana]kasa bo silayo" ("Two slabs of Cuda, the Yonaka").

Around 113 BCE, Heliodorus, an ambassador of the Indo-Greek ruler Antialcidas, is known to have dedicated a pillar, the Heliodorus pillar, around 5 miles from Sanchi, in the village of Vidisha.

War over the Buddha's Relics

The southern gate of Stupa No1, thought to be oldest and main entrance to the stupa, has several depictions of the story of the Buddha's relics, starting with the War over the Relics.

After the death of the Buddha, the Mallas of Kushinagar wanted to keep his ashes, but the other kingdoms also wanting their part went to war and besieged the city of Kushinagar. Finally, an agreement was reached, and the Buddha's cremation relics were divided among 8 royal families and his disciples.

This famous view shows warfare techniques at the time of the Satavahanas, as well as a view of the city of Kushinagar of the Mallas, which has been relied on for the understanding of ancient Indian cities.

Removal of the relics by Ashoka

This scene is depicted in one of the transversal portions of the southern gateway of Stupa No1 at Sanchi. Ashoka is shown on the right in his charriot and his army, the stupa with the relics is in the center, and the Naga kings with their serpent hoods at the extreme left under the trees.

Later periods

Further stupas and other religious Buddhist structures were added over the centuries until the 12th century CE.

Western Satraps

The rule of the Satavahanas in Sanchi during the 1st centuries BCE/CE is well attested by the finds of Satavahana copper coins in Vidisha, Ujjain and Eran in the name of Satakarni, as well as the Satakarni inscription on the Southern Gateway of Stupa No.1.

Soon after, however, the region fell to the Scythian Western Satraps, possibly under Nahapana (120 CE), and then certainly under Rudradaman I (130-150 CE), as shown by his inscriptions in Junagadh. The Satavahanas probably regained the region for some time, but were again replaced by the Western Satraps in the mid-3rd century CE, during the rule of Rudrasena II (255-278 CE). The Western Satraps remained well into the 4th century as shown by the nearby Kanakerha inscription mentioning the construction of a well by the Saka chief and "righteous conqueror" Sridharavarman. Therefore, it seems that the Kushan Empire did not extend to the Sanchi area, and the few Kushan works of art found in Sanchi appear to have come from Mathura.

Guptas

The next rulers of the area were the Guptas. Inscriptions of a victorious Chandragupta II in the year 412-423 CE can be found on the railing near the Eastern Gateway of the Great Stupa.

The glorious Candragupta (II), (...) who proclaims in the world the good behaviour of the excellent people, namely, the dependents (of the king), and who has acquired banners of victory and fame in many battles

— Sanchi inscription of Chandragupta II, 412-413 CE.

Temple 17

Temple 17 is an early Buddhist stand-alone temple (following the great cave temples of Indian rock-cut architecture), as it dates to the early Gupta period (5th century CE). It consists of a flat roofed square sanctum with a portico and four pillars. The interior and three sides of the exterior are plain and undecorated but the front and the pillars are elegantly carved, giving the temple an almost ‘classical’ appearance, not unlike the 2nd century rock-cut cave temples of the Nasik caves.

With the decline of Buddhism in India, the monuments of Sanchi went out of use and fell into a state of disrepair. In 1818, General Taylor of the Bengal Cavalry recorded a visit to Sanchi. At that time the monuments were left in a relatively good condition. Although the jungle had overgrown the complex, several of the Gateways were still standing, and Sanchi, being situated on a hill, had escaped the onslaught of the Muslim conquerors who had destroyed the nearby city of Vidisha (Bhilsa) only 5 miles away.

Western Rediscovery of Sanchi

General Henry Taylor, who was a British officer in 1818 in the Third Maratha War of 1817–1819, was the first known Western historian to document ,in English, the existence of Sanchi Stupa. The site was in a total state of abandon. Amateur archaeologists and treasure hunters ravaged the site until 1881, when proper restoration work was initiated. Between 1912 and 1919 the structures were restored to their present condition under the supervision of Sir John Marshall.

The eastern gateway of the Sanchi stupa

19th Century Europeans were very much interested in the Stupa which was originally built by Ashoka. The French sought the permission of Shahjehan Begum to take away the eastern gateway which was quite well preserved, to a museum in France. English, who had established themselves in India, majorly as a political force, were interested too in carrying it to England for a museum. They were satisfied with plaster-cast copies which were carefully prepared and the original remained at the site, part of Bhopal state. The rule of Bhopal, Shahjehan Begum and her successor Sultan Jehan Begum, provided money for the preservation of the ancient site. John Marshall, Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India from 1902 to 1928, acknowledged her contribution by dedicating his important volumes on Sanchi to Sultan Jehan. She had funded the museum that was built there. As one of the earliest and most important Buddhist architectural and cultural pieces, it has drastically transformed the understanding of early India with respect to Buddhism. It is now a marvellous example of the carefully preserved archaeological site by the Archeological Survey of India. The importance of the Sanchi Stupa in Indian history and culture can be understood from the fact that the Reserve Bank of India introduced new 200 Indian Rupees notes depicting the Stupa in 2017.

Since Sanchi remained mostly intact however, only few artefacts of Sanchi can be found in Western Museum: for example, the Gupta statue of Padmapani is at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and one of the Yashinis can be seen at the British Museum.

Today, around fifty monuments remain on the hill of Sanchi, including three main stupas and several temples. The monuments have been listed among other famous monuments in the UNESCO World Heritage Sites since 1989.

The reliefs of Sanchi, especially those depicting Indian cities, have been important in trying to imagine what ancient Indian cities look like. Many modern simulations are based on the urban illustrations of Sanchi.

Sanchi and the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara

Although the initial craftsmen for stone reliefs in Sanchi seem to have come from Gandhara, with the first reliefs being carved at Sanchi Stupa No.2 circa 115 BCE,[25] the art of Sanchi thereafter developed considerably in the 1st century BCE/CE and is thought to predate the blooming of the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara, which went on to flourish until around the 4th century CE. The art of Sanchi is thus considered as the ancestor of the didactic forms of Buddhist art that would follow, such as the art of Gandhara. It is also, with Bharhut, the oldest.

As didactic Buddhist reliefs were adopted by Gandhara, the content evolved somewhat together with the emergence of Mahayana Buddhism, a more theistic understanding of Buddhism. First, although many of the artistic themes remained the same (such as Maya's dream, The Great Departure, Mara's attacks...), many of the stories of the previous lives of the Buddha were replaced by the even more numerous stories about the Bodhisattvas of the Mahayana pantheon. Second, another important difference is the treatment of the image of the Buddha: whereas the art of Sanchi, however detailed and sophisticated, is aniconic, the art of Gandhara added illustrations of the Buddha as a man wearing Greek-style clothing to play a central role in its didactic reliefs.

The presence of Greeks at or near Sanchi at the time is therefore known ; the Indo-Greek ambassador Heliodorus at Vidisha circa 100 BCE, the Greek-like foreigners illustrated at Sanchi worshiping the Great Stupa, or the Greek "Yavana" devotees who had dedicatory inscriptions made at Sanchi.

SOURCE : Wikipedia